In the Sustainable Development Goal era, the demand for timely and accurate data requires stronger health management information systems (HMIS) in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). While HMIS are a rich data source – with the potential to track subnational, national and global goals toward reducing preventable maternal and newborn health – their data also frequently comes with challenges.

Obstacles include poor data quality and timeliness, as well as a disconnect between the type of data that would be useful for strengthening health system, and the type of data that is actually collected. To better understand the maternal and newborn health data captured in the routine HMIS of USAID-supported LMICs, MCSP and its predecessor – the Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (MCHIP) – conducted content analyses four years apart.

Both analyses highlighted the strengths and weaknesses in the available data with an eye toward improving information systems. The 2014 MCHIP review included 13 countries and reviewed data elements related to antenatal and delivery (intrapartum) care. Under MCSP, the scope of the 2018 review was expanded to 24 countries and included postnatal care.

Recently, we compared findings from the two reviews to ask: are there signs that the availability of key data elements is improving over time?

Twelve countries were included in both reviews: Bangladesh, Ethiopia, India, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Nepal, Nigeria, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda. We selected 10 data elements that were common to both reviews and part of global guidance documents around maternal and newborn health metrics:

- HIV testing for pregnant women and their partners (either whether the test was conducted or the test result was recorded) during antenatal care;

- Blood pressure measurement during antenatal care;

- Uterotonic for postpartum hemorrhage prevention immediately after birth;

- Incidence of maternal complications, including postpartum hemorrhage, pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, and sepsis;

- Breastfeeding initiation within one hour; and

- Incidence of newborn complications, including preterm birth and asphyxia.

Regarding data that is captured in health registers (data that remains in the individual facilities, typically recorded on paper), we found the following areas of improvement:

Antenatal Care:

- 9 of 12 countries tracked HIV testing of pregnant women in 2014, and this increased to 10 of 12 in 2018.

- Three additional countries (8 of 12 total) started tracking HIV testing for pregnant women’s partners.

- One country (Kenya) added blood pressure measurement, bringing the total number of countries recording this information to seven.

Labor and Delivery:

- Uterotonic for postpartum hemorrhage prevention was tracked by only two countries in 2014, and this increased to five countries in 2018.

- Recording of breastfeeding initiation within the first hour increased from five countries in 2014 to 10 countries in 2018.

- Three more countries (8 of 12 total) began tracking preterm births, and two more starting counting neonatal asphyxia (7 of 12 total).

- Regarding maternal complications, both reviews found 8 of 12 countries counting postpartum hemorrhage, recording of eclampsia increased from six to seven countries, and maternal sepsis cases rose from four to six countries. However, not all countries specified the timing of complications (whether they occurred during the antenatal period, at the time of birth, or postnatally).

The summary forms, which are aggregated to higher levels of the health system, reveal fewer changes: one more country reported on HIV partner testing (5 of 12 total), three more countries tracked breastfeeding in the first hour after birth (9 of 12 total), and one country added postpartum uterotonic (2 of 12 total), preterm birth (6 of 12 total), and neonatal asphyxia (5 of 12 total). No increases were found in the other data elements.

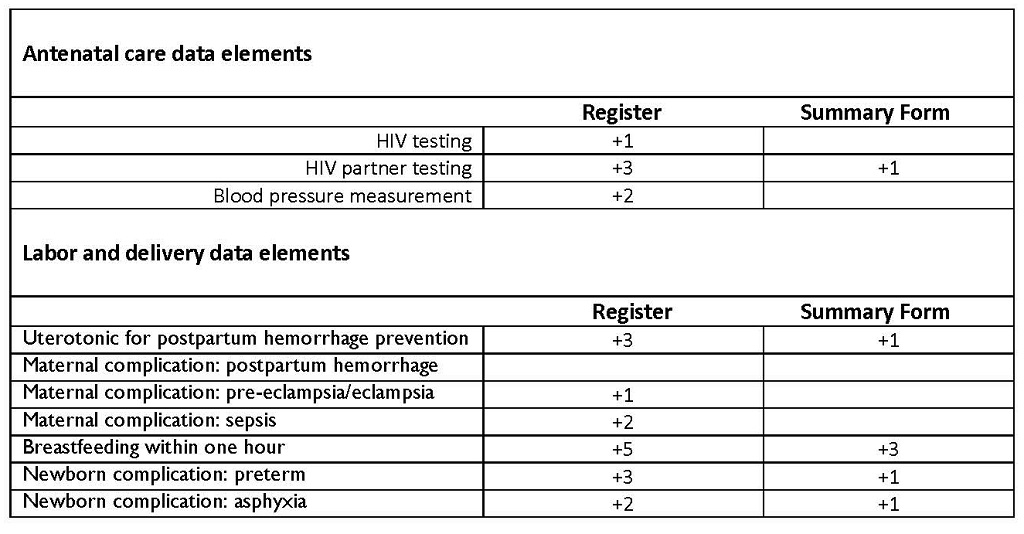

The table below shows, out of 12 countries, the increase in countries reporting from the MCHIP to the MCSP review:

Although these reviews have highlighted crucial gaps, giving us all an advocacy agenda for areas needing improvement, we can also see signs of progress: in systematizing efforts to strengthen data quality; in making data available electronically and in real-time; and in strengthening maternal and newborn health metrics globally. All suggest that momentum is building for better data to target efforts to further reduce global maternal and newborn deaths.