This content originally appeared on the Frontline Health Workers Coalition website.

Yustina Emmanuel is making her last home visit of the week.

Her aim is to meet with the housemaid who works here: a 14-year-old who spends her days cleaning, cooking, and caring for her employer’s children—instead of attending school.

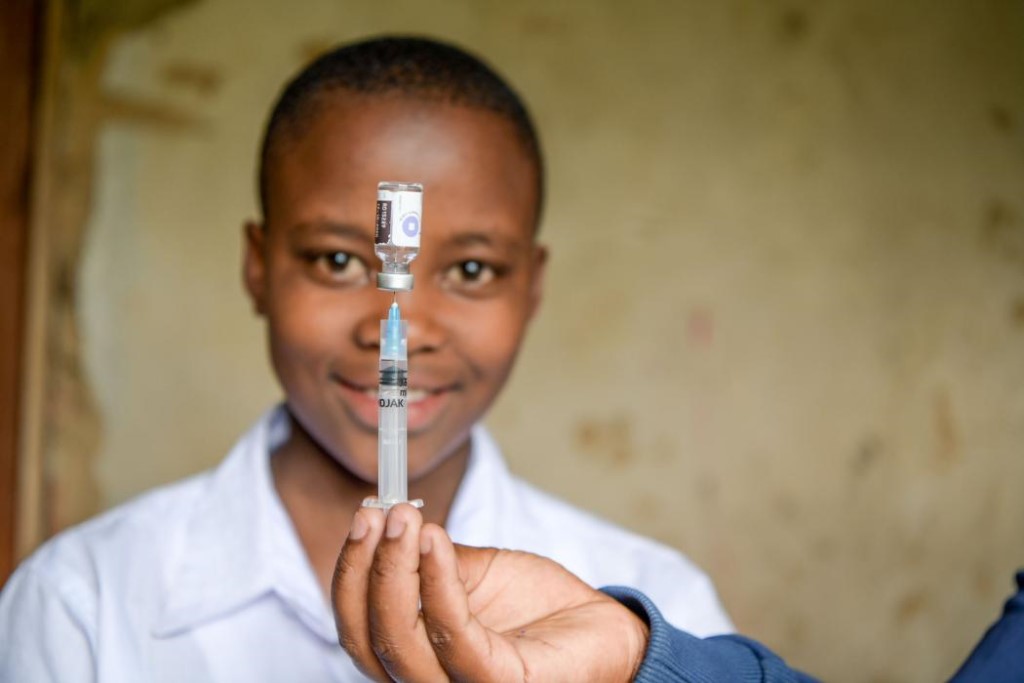

Yustina wants to know if the girl has heard of the HPV vaccine, which others her age are being offered in classrooms nationwide.

An assistant medical officer working in the Iringa District Council of Tanzania, Yustina invites both the housemaid and her employer to listen and ask questions. She explains what HPV is and how it relates to cervical cancer: HPV is a common sexually transmitted virus that can cause cervical cancer, the number 1 cancer killer of women in Tanzania.

Cervical cancer can be prevented, Yustina assures, adding that the best protection is vaccination.

Before leaving, Yustina writes down her mobile number and speaks to both the girl and her employer, encouraging the employer to follow up to facilitate the girl’s visit to the local health facility where she can get the HPV vaccine.

Since Tanzania launched its national HPV vaccination program in early 2018, Yustina regularly makes house calls like this one with the goal of ensuring that all 14-year-old girls receive the requisite two doses of the HPV vaccine. This innovative, first-of-its-kind vaccine could eliminate cervical cancer from the next generation, but only if countries are willing and able to protect all girls.

To efficiently reach the greatest number of 14-year-old girls, Tanzania’s national program focuses on in-school vaccination campaigns. But this approach misses the crucial point that not every girl is in school. Which is why Yustina is intent on finding and counseling girls wherever they are, and why frontline health workers like her are so integral to the success of the program.

“I track young housemaids who have finished standard 7 [a school grade], who are employed in my area,” Yustina says.

According to UNICEF, in Tanzania, 3.9 million school-age children and adolescents are not attending school: 23.2% of 7-13 year old girls; and 40.9% of 14-17 year old girls. Out-of-school girls often come from vulnerable communities in rural areas and are at a higher risk of early sexual debut, and acquisition of sexually transmitted infections, including HPV. Girls in these circumstances who later develop cervical cancer likely will face big barriers to accessing treatment, which makes the equitable distribution of the HPV vaccine so critical.

Girls who are not attending school present a great challenge for vaccinators, said Tatu Said Rashid, a registered nurse working in the same area as Yustina. Conventional non-school-based approaches—such as waiting on girls to visit local Reproductive and Child Health facilities and depending on community leaders to convince families of the power of immunization—have fallen short.

“Few out-of-school girls actually come to the clinics on their own to be vaccinated,” she explains.

Worldwide, countries have struggled to both identify and reach out-of-school girls with the vaccine. Of 46 countries that conducted demonstration projects, 42 delivered the vaccine through school-based programs, with minimal or no outreach or facility-based vaccination. Among low- and middle-income countries that have begun national HPV vaccine introductions, the majority are utilizing a school-based delivery approach. Emerging data from monitoring reports indicate that coverage among out-of-school girls is grossly inadequate.

Supported by Tanzania’s Ministry with implementing partners like Jhpiego, extensive outreach activities are improving vaccine uptake by vulnerable girls, especially those not attending school. This makes Yustina and Tatu hopeful. They report that when girls and their parents learn about the vaccine’s importance and safety, most want protection against cervical cancer—not only for themselves but also their friends. A number of girls they have counseled have shared the information with others who are out of school.

Now in its second year, the national vaccination strategy emphasizes equitable coverage for all, which gives ample reason for Yustina and Tatu to remain on the front lines, ferreting out the hardest-to-reach girls by knocking on doors—before cervical cancer has a chance to find them.