This blog originally appeared on The Huffington Post.

Community engagement is one of many promising approaches central to changing social norms and behaviors. It improves women’s decision making power, builds community capacity, addresses issues of equity, strengthens social cohesion, and improves knowledge, skills and health care seeking practices.

However, changing peoples’ behavior is never easy, because it is intertwined with a complex set of social and cultural norms, structural and faith influences. Community engagement rebuilds peoples’ belief and trust in their own health systems, which is fundamental to stronger demand and utilization of health care services. And in most communities, faith actors and institutions play a critical role in influencing communities.

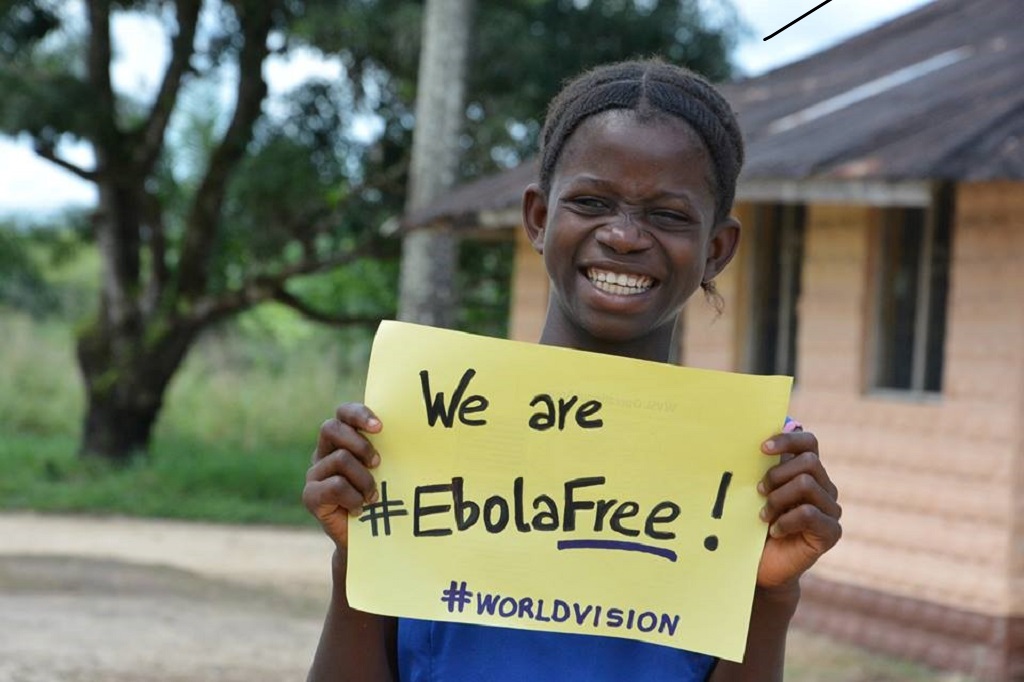

A post Ebola epidemic study commissioned by World Vision in Sierra Leone shows that roughly 70% of respondents reported receiving information on prevention from religious leaders. This is perhaps in part due to World Vision’s efforts to organize and build the capacity of religious leaders to include key messages about prevention and treatment during sermons – such as during Friday prayer at mosques and Sunday church services – which emerged as key opportunities.

A common acknowledgement was that prevention requires a community-wide response that engages community leaders from the onset. The study also found that the most influential people in stopping the spread of Ebola were people within the community (80.0% case vs. 36.4% control) and community health workers (93.3% case vs. 54.5% control). Case households were also statistically significantly more likely to send a family member to an Ebola treatment unit or health care facility (92.3% versus 60.9%).

Likewise, in Kenya, a three-year maternal and child health (MCH), advocacy, and birth spacing project showed that religious leaders acted when they recognized the importance and impact of timing and spacing of pregnancies on MCH. They championed and delivered health timing and spacing of pregnancy (HTSP) messages to their congregations and promoted support from male spouses.

Referrals by a religious leader led to 6,086 women attending a health facility to seek HTSP, family planning, or MCH services; more than half of these women decided to use a method of contraception. The end line contraceptive prevalence rate was 69.5% – a 20% increase from a baseline of 49.5%, mostly due to community health worker messaging in households and referral to health facilities.

Clearly, investment in and engagement of trusted local community members can enhance a community’s trust, which is central to change, mitigates false assumptions, and provides key actions to be undertaken at the household and community levels. Behavior change approaches that engage different community actors – including faith groups – and incorporate messages that address social and faith influences is paramount to address entrenched belief systems.