What will it take to eliminate malaria for good? We must ensure that all pregnant women and children under five in malaria endemic areas have access to preventative, diagnostic and treatment services. And this begins with assessing the status of this goal in the world’s hardest hit countries.

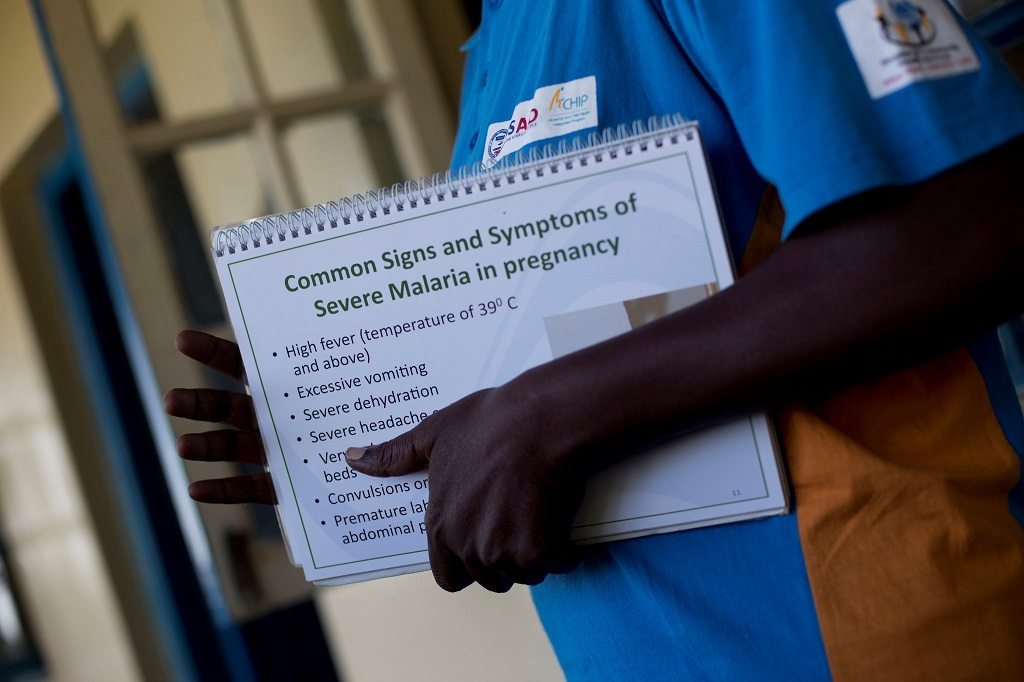

Each year in sub-Saharan Africa, malaria in pregnancy (MiP) is responsible for 20% of stillbirths and 11% of newborn deaths, resulting in an estimated 10,000 maternal deaths and 100,000 newborn deaths. In addition to its impact on maternal and newborn deaths, MiP contributes to devastating outcomes for pregnant women and their newborns, including maternal anemia, stillbirth, spontaneous abortion, and low birth weight.

In 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) revised its MiP (IPTp) policy recommendation for sub-Saharan African countries with moderate to high endemicity to provide IPTp with sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) to all pregnant women not taking cotrimoxizole prophylaxis starting as early as possible in the second trimester, and to deliver a dose at each subsequent antenatal care (ANC) visit at least one month apart until delivery. The global target for pregnant women to receive at least three doses of IPTp is 100%, while national targets are at least 85%.

Twelve new MiP country profiles allow us to better understand the current status of MiP program implementation in US President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) countries – as well as the progress achieved in ensuring IPTp coverage among pregnant women. Developed by MCSP in coordination with PMI and the Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the profiles explore progress towards attaining targets, review countries’ IPTp guideline alignment with the updated WHO recommendations, and document countries’ efforts to implement and monitor policy changes. They also highlight best practices across the region that may inform policy and practice in other countries with the aim of improving MiP interventions, specifically IPTp coverage rates.

Policy and Implementation

Of the 19 sub-Saharan PMI countries reviewed, in-depth profiles were generated for 12. Of these, five countries’ policies are unclear: three still mention quickening – when a fetus’ movements are first felt; a fourth country lists IPTp initiation at 14 weeks; and a fifth recommends starting IPTp anywhere from 13 to 16 weeks. Several countries reported strong, coordinated leadership around MiP, including Senegal, Burkina Faso, Ghana and Malawi – countries that have delivered strong IPTp coverage despite the absence of either an MiP technical working group or clearly written IPTp policy.

Service delivery

Among the 12 countries profiled, the average percentage of women receiving at least two doses of IPTp was 46%, according to the most recent household survey; however, coverage ranged broadly from 15% in DR Congo to 78% in Ghana. The percentage of pregnant women who report sleeping under insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) also varied widely, averaging 55% in the 12 countries reviewed. In Zimbabwe, 25% of pregnant women reported sleeping under an ITN compared to 77% in Burkina Faso.

It is notable that there is no apparent correlation between a country’s IPTp2 and ITN coverage, with some countries excelling in one area and struggling in the other. Additionally, recent health management information systems (HMIS) data indicated that some countries have significantly improved coverage of interventions that may not yet be reflected in household survey data, which is now several years old. Many countries are still working to implement MiP policies and programs consistently and with quality in the private sector.

Community Engagement

Nearly all 12 countries have engaged communities with promotion of MIP efforts and interventions. These ranged from outreach activities encouraging ANC attendance and IPTp uptake to provision of ANC and IPTp services by mobile health staff or community health workers. For example, Benin deployed ANC outreach services in areas identified as having low coverage of interventions including IPTp. Similarly, Ghana’s Community-based Health Planning and Services program provided access to community health nurses and midwives in select communities. Nigeria also reported several small-scale outreach activities that provide services to pregnant women at household level.

Community delivery of IPTp (C-IPTp) was being piloted in five countries reviewed: Burkina Faso, DR Congo, Madagascar, Malawi and Nigeria. (C-IPTp is also being piloted in Mozambique.) Additionally, Zimbabwe had recently revised its national policy to include C-IPTp as a strategy in IPTp-implementing districts, and is expected to begin implementation soon.

Commodities

Most of the 12 countries continued to struggle with SP stock-outs at the peripheral level, whether ongoing or episodic, with many health facilities experiencing stock-outs despite SP availability at the central level. Several governments, including those of Burkina Faso, Ghana and Kenya, prioritized government resources for procurement of SP. Meanwhile, in Angola and Malawi, donor-procured malaria commodities have been removed from the integrated government supply chain to improve transparency and accountability.

Monitoring and Evaluation

In these profiles, household survey data have been used to track progress towards IPTp coverage goals, as the data are representative and standardized. Most countries also use health facility data collected by HMIS to track the numbers of pregnant women attending ANC who receive IPTp. As IPTp policies have changed to recommend more than two doses of SP during a pregnancy, the relevant indicator(s) reported by HMIS have also changed in some countries from IPTp2 to IPTp3.

Inconsistent HMIS indicators complicate tracking progress in intervention implementation. Other measurement challenges include appropriately identifying women eligible for IPTp in areas with high HIV prevalence (as IPTp is contraindicated when taking cotrimoxazole as recommended among HIV-positive pregnant women), and monitoring coverage in countries with subnational malaria policies.

What stands between more needless deaths and elimination of a disease that threatens nearly half of the world’s population? Reaching the “unreachable.”

Overall progress on IPTp coverage was seen in all 12 PMI countries; however, with the transition to monitoring and reporting on IPTp3, a renewed focus on uptake of IPTp3 will be needed both to ensure that countries have clear and consistent policies, staff trained, and commodities available to support progress to targets.

Countries must also ensure that MiP indicators are correctly and appropriately integrated into routine reporting systems to track the data needed to monitor progress, including disaggregation of case management data by pregnancy status and ITNs distributed through ANC visits. Countries with higher IPTp coverage reported government leadership’s commitment to malaria in general and MiP specifically as a priority, indicating that high-level advocacy efforts may assist countries still struggling to improve coverage.

At both community and facility levels, MCSP is building on our successes – and learning from the challenges revealed in these profiles – to propel our malaria programs to the next level.

To learn more about these country profiles, click here to watch an MCSP webinar.