Nampula Province, Mozambique – By 36 years old, Joaquina Lapsone had given birth to 11 children, all at home. When she met Petacosta Adriano and Angelina Manuel – two MCSP-trained community health committee (CHC) members – she was 6 months pregnant again, although she did not want to be. Like many Mozambican women, she faced challenges convincing her partner to use family planning (FP) methods.

Petacosta and Angelina learned about Joaquina’s history during a home-based reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health (RMNCH) education session she attended with her husband, Silvestre, and other community members. These sessions are part of MCSP’s efforts in Nampula and Sofala provinces to engage men in encouraging their family to seek health care while transforming harmful gender norms that unfairly put the burden of the family’s health on women.

Sitting in the backyard of the couple’s house, Petacosta and Angelina told Joaquina that she was at high risk for complications due to the number of children she had delivered and the short intervals between her pregnancies – 11 children since she was 18-years-old. With her health history, she was likely to suffer from uterine rupture, postpartum hemorrhage, eclampsia, and giving birth to a premature, low birth weight baby, they said.

The CHC members counseled Joaquina and Silvestre together on birth preparedness and complication readiness (BPCR) to help them understand the danger signs during pregnancy; the importance of attending antenatal, postnatal and postpartum care, and delivering at a health facility; and the benefits of FP. The BPCR strategy aims to reduce delays in care seeking, promote skilled birth attendance, and facility deliveries. It allows couples to jointly prepare and plan the logistics surrounding the delivery (including emergency transportation), and to address gender inequalities that inhibit access to care.

In households where men control spending and decision-making, they are often resistant to giving women permission and money to go to a health facility, including for antenatal care (ANC). In the case of Joaquina’s husband, the counseling session led him to accept all aspects of the BPCR strategy—with the exception of adopting an FP method. For religious and cultural reasons, he said, the family would continue to not use FP.

A month later, when Petacosta and Angelina visited the couple for a second time, they reinforced the importance of FP for the health of the entire family. Joaquina again expressed her desire to stop having children, but her husband continued to resist, citing myths he had heard that FP causes infertility. The trained counselors worked to dispel his misconceptions, explaining that families with fewer children are healthier, live longer, and can afford to feed, educate and support their children.

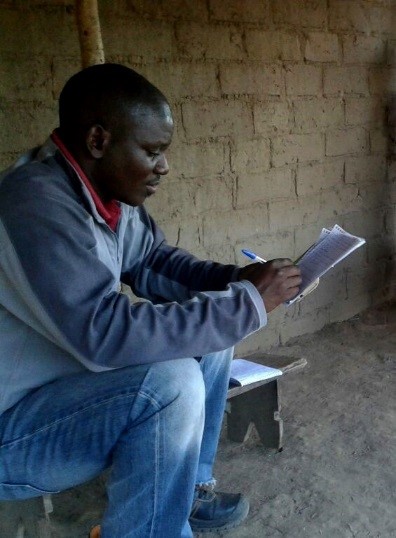

During a supervision visit a few weeks later, two additional MCSP employees – Zaida Macie, an MCSP Community Gender Officer, and Fastel Ramos, an MCSP Community Monitoring & Evaluation Officer – paid a third visit to the couple. By this time, Joaquina and Silvestre had initiated a birth plan and completed two ANC visits, per the previous counseling. Moreover, following the steps of the BPCR plan, they knew the probable month of the birth, had bought clothing for the baby, identified family to care for their children during their absence, and saved money to rent a motorcycle to transport them to the health facility, if necessary.

Convincing Silvestre to support his wife’s desire to use postpartum FP remained a challenge; however, Zaida did not give up. Once more she stressed the risks that Joaquina would face if she became pregnant again as well as the benefits of using modern FP methods. When Silvestre finally understood the dangers to their newborn – and the possibility that another birth could kill his wife – he at last accepted FP.

Early one evening the following month, Joaquina’s labor began. Because Silvestre had arranged for motorcycle transport in advance, she was able to reach Iapala Monapo Health Center – about 15 kilometers (9 miles) away on a bumpy dirt road – where she had a normal delivery with no complications. Twenty-four hours later, she and her newborn son, named Soneque, were discharged and returned home with Silvestre.

“Thanks to the birth plan, I had a safe delivery at the health facility,” Joaquina said. “My son was born well.”

To add to this happy ending, Joaquina and Silvestre chose tubal ligation for their FP method, having decided together that they do not want any more children.

“We are happy for the visits of the health committee and the counseling from the experts who came to visit us from time to time,” Joaquina said during a postpartum visit. “To this day, [my son] and I are in good health — different than the previous births that happened at home with much suffering.”

Since 2015*, MCSP has reached thousands of community members in Nampula and Sofala provinces with educational messages about male involvement in RMNCH. This includes 1,358 clinical providers and managers from 86 health facilities, and 758 community health committees (comprised of 11,310 individual community health committee members). We’ve sensitized 31,424 community members on male engagement on RMNCH (including BPCR), and supported 5,185 couples to develop birth plans.

By involving men like Silvestre in the health of their families, MCSP is transforming traditional gender norms in Mozambique that act as barriers to RMNCH services – one father, one mother, one family at a time.

** Numbers as of December 2017