This blog originally appeared on The Huffington Post.

A great challenge for health systems across the world is simply having the people and infrastructure to deliver care to all those who require it. For many people, the nearest health facility may be far away and crowded. Hospitals and health centers tend to focus on curative rather than preventative services. As a result, many people have limited access to health services — especially important preventative measures, like family planning and vaccinations – or they receive sub-standard care within overburdened health systems.

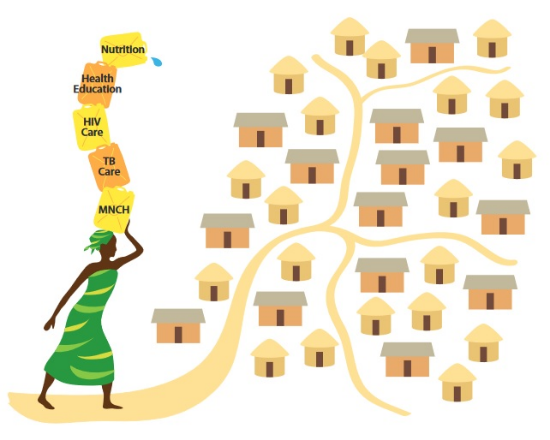

In response to this need for better primary care, a number of governments have established community health volunteer and worker (CHW) programs to bring health services directly to individual households. CHWs have been successful in creating awareness and providing preventative care, and over time they have been tasked with new responsibilities. However, as their role has expanded, CHWs have been strained to reach the hundreds of households they are expected to cover – even those few CHWs fortunate enough to be provided with the local leadership and financial support.

Working to increase vitamin A supplementation in Nepal, I observed that communities possess their own informal support and social welfare systems where community members make decisions and work together to improve the health of members and the general welfare of the community. At first you cannot see that system from the outside, but people within the community use that system to do a lot of things, from managing disasters to organizing festivals. This system consists of existing community groups – such as a village government, schools, religious groups, youth groups, women’s group, agricultural groups, and savings and credit” groups – as well as influential people within the community.

Through my work on the ASSIST Project, we have developed a Community Health System Strengthening Model that brings together formal and informal pre-existing structures and networks to support and amplify the approach of CHWs. By tapping into the structures already in place in the community, CHWs are able to reach every household and, therefore, every individual in a more rapid, effective and sustainable manner.

When starting up, trust is huge problem. Many communities and villagers are distrustful of outsiders because too many projects have come and gone. In the past, we in the development community used to go in and say: What is your problem? Here is the solution. This approach makes people passive.

But when we apply the Community Health System Strengthening Model, the quality improvement intervention is managed by representatives from each community group, health facility representatives, and delegates from the local government who all come together to serve as the community improvement team that identifies local health gaps and develops and tests strategies to overcome those gaps. This model also helps to develop a platform at the community level for engagement to address such emergencies as disasters and epidemics, thus creating more resilient communities.

Once this system starts working – when all elements of the model are harmonized and functioning well and coordinated with the efforts of community-based care providers – health services become more accessible to community members, and accurate information exchange between health facilities and households occurs more rapidly and effectively.

We have applied this model with great results in Ethiopia, Mozambique, Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi and Botswana. By engaging the existing structures in the community, we can leverage the important work of CHWs to reach more people for services than by community health providers working on their own.