Imagine you’re a mother who just gave birth to a 28-week-old baby. If you live in a high-income country, there’s a 90% chance your baby will survive and go home with you. If you live in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, there’s a 90% chance your baby will die within the first few days of life.

Preterm birth is now the single largest cause of under-five mortality.

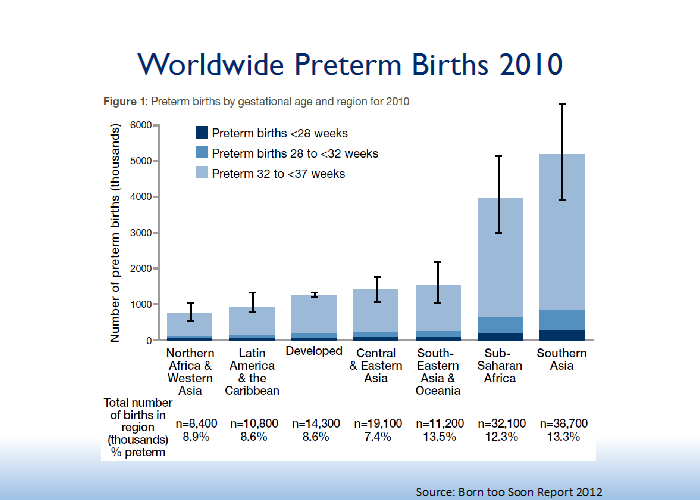

Each year, an estimated 15 million babies are born premature worldwide—a number that’s growing. Moreover, nearly a million premature babies die before their fifth birthday, usually within the first month of life. Although preterm birth is a problem in every country, low-income countries are disproportionately affected, as they have both higher rates of preterm birth and lower rates of survival.

We know how to reduce deaths from preterm birth – now we must translate that knowledge into action at scale with quality.

Three-quarters of preterm babies could be saved with current, cost-effective interventions. In August 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) released the first ever set of recommendations on management of women with threatened preterm birth and care of preterm babies. Based on these recommendations, USAID’s flagship Maternal and Child Survival Program (MCSP) collaborated with the WHO to develop a summary document of highlights and key policy and program considerations for implementing the new guidelines.

As a global program for maternal, newborn and child health, MCSP is uniquely positioned to apply these guidelines to improve services for women and preterm babies. We work across the continuum of a woman’s reproductive life:

- Providing guidance and services for healthy spacing and timing of pregnancies;

- Providing high-quality pregnancy and childbirth care, including preterm birth care;

- Strengthening care for low birth weight and premature newborns with Kangaroo Mother Care; and

- Caring for unstable small babies through innovative interventions, such as bubble continuous positive airway pressure.

Improving outcomes for premature babies requires

more than training health workers.

Although skilled health workers are critical, we must address issues beyond training—such as availability of essential supplies and commodities, organization of and linkages between services, and the cultural practices and expectations that influence the survival of premature babies. The survival of a premature baby is influenced by interventions during pregnancy and after birth; therefore, we must coordinate care for pregnant women with threatened early delivery and their premature babies.

Context also matters for bettering care.

Antenatal corticosteroids (ACS) highlight this importance. In the context of high-resource settings, this medication has reduced the severity of respiratory distress syndrome, a leading cause of death for premature babies. In settings with high-quality maternal and postnatal preterm birth care, the use of ACS in women with threatened early birth between 24 to < 34 weeks of pregnancy has been associated with an average mortality reduction of 30% for preterm infants.

However, recent evidence demonstrates that this potentially powerful intervention may not produce the same results across all settings. When ACS were widely employed for women with threatened preterm birth in six low-resource countries, the 2014 Antenatal Corticosteroids Trial showed increased neonatal mortality in larger infants, and no effect in smaller infants.

There are two leading hypothesis as to why this was the case: the wrong women were getting ACS (poor maternal care); and inadequate postnatal preterm birth care was provided. The recently released WHO preterm birth guidelines clarify several pre-conditions for ACS use in low-resource settings, including availability of special care for the preterm baby. Maternal and newborn health providers must work together to ensure adherence with these recommendations to achieve better outcomes.

In collaboration with WHO, MCSP is developing policy briefs on basic newborn resuscitation and optimal feeding of low birth weight infants in low- and middle-income countries. These documents will complement existing WHO guidelines on both topics.

Maternal and newborn health providers must work together to

improve survival of premature babies.

At MCSP, we’re actively promoting improved coordination of maternal and newborn care services to ensure that women with threatened preterm birth and preterm infants receive high-quality care. One way we know to achieve this is through the formation and support of perinatal teams: a mix of all cadres impacting maternal and newborn care, coordinating care and addressing gaps to improve quality.

MCSP also contributed to the development of Helping Mothers Survive and Helping Babies Survive training packages. The maternal preterm birth package, due for release this December and led by MCSP, focuses on actions to be taken during pregnancy and labor when preterm birth is expected. The newborn package focuses on care for the small preterm newborn.

Across the globe, our maternal, newborn and family planning teams are working together to strengthen harmonized maternal and newborn care services. Together—and in coordination—we’re moving closer to ending all preventable preterm deaths.