Parents in rural Ghana know their kids’ brains — and community’s future — depend on child play.

DoDoo Street, the dirt road bisecting Siriyiri, is bustling on this early Monday morning. A motorized tricycle known as yellow-yellow discharges women near a roadside stand, its shelves filled with bags of millet and shea butter balls.

They walk with purpose, joining others arriving by foot, many wearing babies wrapped in vivid cloth.

All veer off-road, down a path through the grass, past the single bore hole on which this community of 1,428 depends.

I’m eager to follow, to stretch my legs after three flights and a half-day’s drive landed me in this village surrounded by savanna in Ghana’s Upper West. Everyone, I assume, is making their way to the mother’s group gathering that Mousa Ali of the Ghana Health Service and I have come here to see.

But no.

As our car parks in front of the yellow-yellow, whose driver has settled in for a nap, Ali answers a call and learns that two Siriyiri residents have died.

The mothers’ group is cancelled, he says apologetically. The women who regularly gather to learn about childhood nutrition – including exclusive breastfeeding and infant and young child feeding – will instead take part in a deep-rooted community practices: the solemn shaking of hands and sharing of pito, a local brew of fermented millet. The early childhood development lessons, toy-making, and toddler games will also have to wait.

Above: Pito for all.

Clearly, locals heard the news before we did, and dropped everything to come and grieve with the bereaved. Men sit under that tree, women under this one.

The rains have ended. It’s harvest season for millet, maize, cow peas, and ground nuts. But work will wait.

So, too, will play.

Above: Sakina (left) and community health volunteer Howa Braimah.

On DoDoo Street, I chat with two women who would have attended today’s mother’s group had two funerals not preempted it. A mother named Sakina credits Howa, the community health volunteer who leads the local group, for teaching her new things about her 2-year-old: his brain is developing now, and he needs nurturing and stimulation from her to thrive.

Eager to show me a bit of what she’s learned, Sakina locks eyes with her son and sings while touching his nose. He giggles in anticipation of a toss topped off by a hug.

This sweet demonstration reveals the essence of an effort by MCSP with the government of Ghana to counteract generations of poor health and low educational attainment. These responsive parenting lessons are folded into larger efforts aimed at “nurturing care,” which stresses adequate nutrition, and security and safety – all components needed for babies to survive and thrive.

The gist is to integrate early childhood development lessons into existing health and nutrition activities. Why? Because evidence shows that investments in the early years yield high rates of return to families, communities and countries.

Delightful as the mother-son moment is, it’s missing the magic of peer support. Camaraderie is a cornerstone of the early childhood development sessions as designed and promoted by MCSP. The strategy involves training front line health workers to practice stimulation techniques with entire communities. It’s all about encouraging playful learning in the context of lots of company. This is why the parents of Siriyiri gather monthly to sing infant songs and play toddler games, each impressing on the others that these activities are neither trivial nor abnormal.

Across Ghana, it’s unusual to speak to babies before they can talk or actively engage. In fact, violent discipline of toddlers and children is common and widespread. But here, child’s play is becoming a village norm — like the paying of respects. Parents now see it as a building block of community.

Above: The building blocks of community.

Perched on a pile of bricks that will become a local home or family compound, Sakina – who learned about the importance of breastfeeding in the mother support group – nurses her son, now played-out and thirsty. Meanwhile, Ali consults with MCSP’s Kamil Abdul Salam, who oversees the Program’s early childhood development activities in this region.

In the two regions of Eastern and Upper West, MCSP has reached 196 mother-to-mother support groups and 911 communities with the kinds of messages that Sakina has taken to heart. It’s also institutionalizing the content by reviewing and influencing key government policy — including the National Newborn Strategy, National ECCD 0–3 Standards.

Above: Peek-a-boo.

Determined to show me a mother’s group in action, Ali and Salam propose driving 90 minutes east to Sigri, also located in Jirapa, Ghana’s least developed district. A group is scheduled to meet there this afternoon.

Before leaving, we follow a path into the village to shake hands with the families whose loved ones just passed. Back on DoDoo street, we exchange a few Ghanaian cedi for a bunch of bananas and a couple balls of raw shea butter.

Above: A fatty oil extracted from tree nuts, shea butter stays solid even in

Ghana’s wilting midday heat.

Then, we are off to Zingpen, population 982.

To ensure that childhood development lessons reach everyone from urban professionals in Accra to village farmers in Zingpen, MCSP works with the Ghana Health Services’ Ministry of Gender and Children and other government agencies to train a wide range of community health officers, front line health workers, and volunteers.

At the Ghana Health Service Community-Based Health Planning and Services (CHPS) compound in Sigri, we stop to pick up Mariam Ouateura, a local nutritionist whose advice parents trust. Her words carry weight.

Above: Mariam Ouateura.

When she says that play nourishes self-esteem and intellect, the community listens. Regularly scheduled mothers’ meetings like the one today give her an opportunity to integrate lessons about brain stimulation with more traditional health outreach — such as promoting exclusive breastfeeding for optimal weight gain. The combination of appropriate nutrition and brain stimulating activities ensure that the child’s brain development is optimal, especially during the period of its most rapid growth from 0-3 years.

Above: Going out on a limb to get weighed.

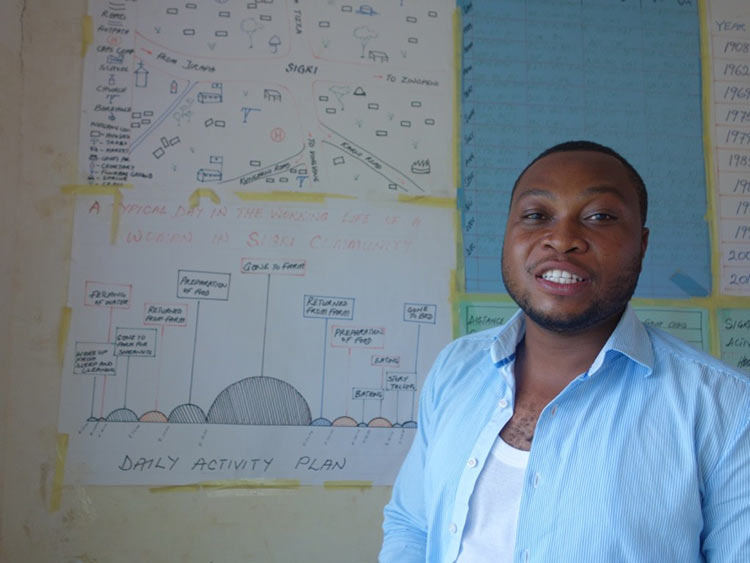

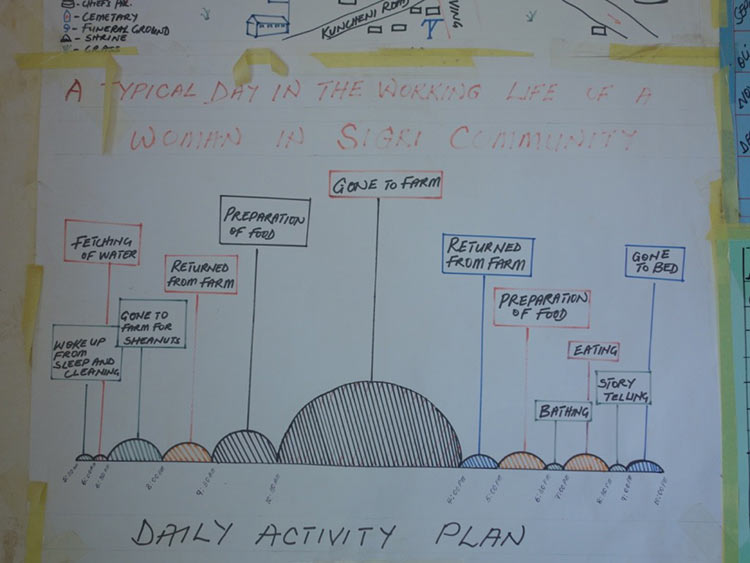

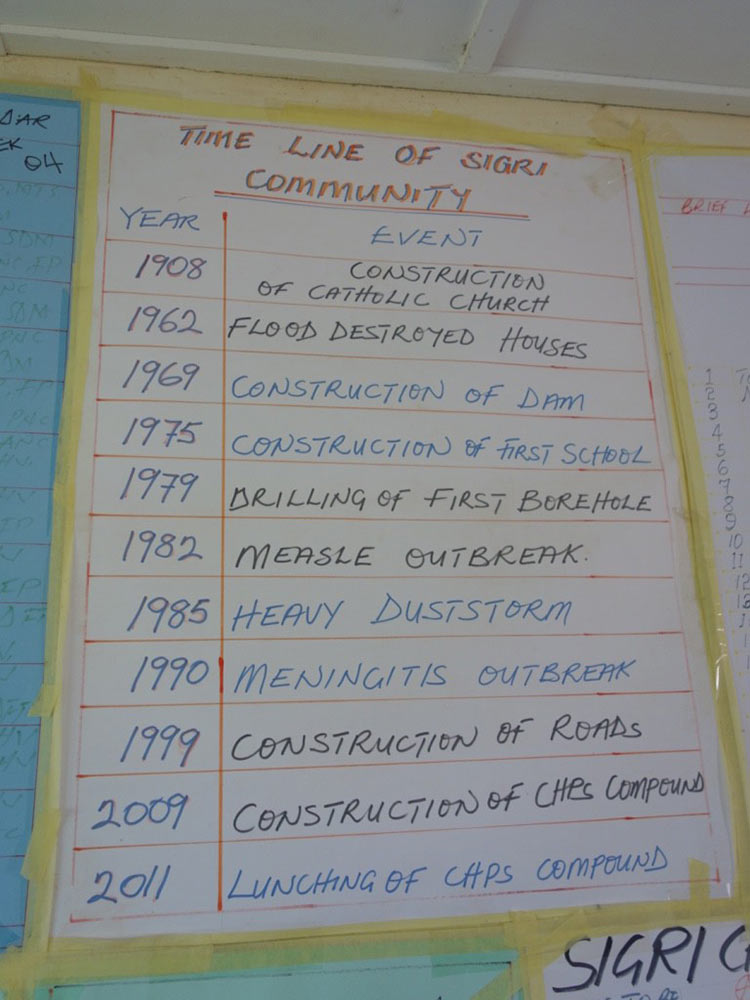

As Ouateura gathers her things, Ali points to the hand-drawn maps, charts and timelines that cover the walls of this facility. They reveal who lives where in this village, its history, and a typical day’s activities.

Above: Mousa Ali, deputy regional CHPS coordinator for the Ghana Health Service.

Understanding the natural rhythms of local life is key to offering the right services at the right time and place, the deputy regional CHPS coordinator says.

Evidently, the time for play is now, and the place is under a neem tree, where a crowd has gathered.

Above: The Zingpen “mothers” group welcomes dads, too.

Thirty-two women, a half dozen men, and 19 babies and kids are enjoying the shade, likely thinking this is simply session №3 in the early childhood development series. But to my eyes and ears, this is a happening – one that could cause widespread fear of missing out (FOMO) well beyond Zingpen.

Above: Videos capture my warm Wa West welcome – including trilling!

Ali, Ouateura, Salam and I join in the clapping, singing and dancing, but we leave the trilling, impeccably timed, to a local.

Above: Video of the housewives of Zingpen calling the mothers group to order.

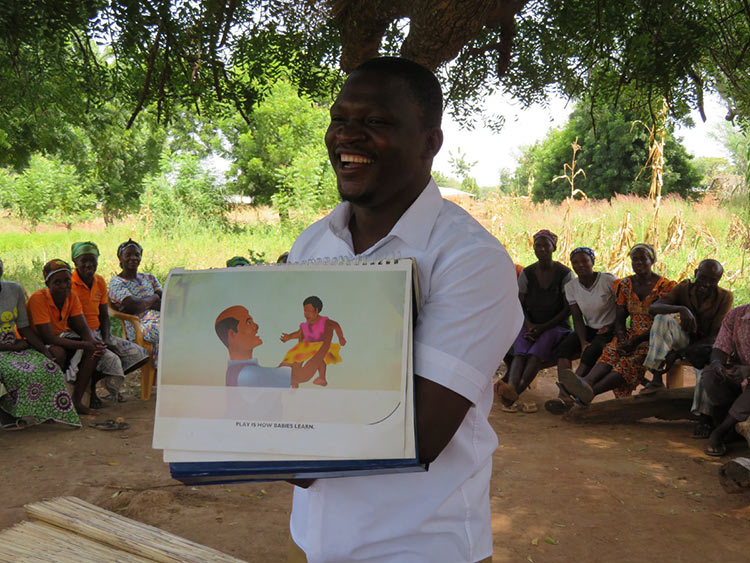

Nurse Mohammed Omar, an MCSP-trained community health officer, invites everyone to take a seat. He speaks in the local dialect, using a flip book printed in English but illustrated with drawings that all can understand.

Above: Nurse Mohammed Omar shares his play book with the crowd.

“Touch builds strong bonds” he reads, showing a picture of a woman with a child. “Play is how babies learn,” appears in text beneath a picture of a man holding a baby girl. There’s enthusiastic clapping each time someone answers a question he poses.

Above: Video of the Nurse Omar explaining how babies learn.

Below: Video of Nurse Omar answering the community’s questions.

Today’s focus is on engaging toddlers with games that involve their whole bodies. Toddlers want and need to help their caregivers, Nurse Omar says as he calls on Portia Gbiel to step forward. The mother hands off her own baby, 3-month-old Bethetile, and does proper handwashing before demonstrating whole-body play with a neighbor’s toddler.

“When my older child was a baby, I didn’t know that playing is important to brain development,” Gbiel says, referring to her firstborn, who is now five. “But when I started coming to early childhood development sessions, I learned that even during pregnancy I could play with my child.”

Above: Video of Gbiel dancing with her toddler.

While pregnant, Gbiel sang to the unborn Bethetile. Her husband also talked and touched her stomach tenderly in response to the developing baby’s kicks.

What once seemed odd began to feel natural.

The couple enjoys playing with Bethetile, Gbiel says. It’s noticeable how much the baby benefits, she adds, admitting, “I’ve realized there’s a difference between this child and my older child.”

Her friends and neighbors clap in approval. While she takes her seat, Nurse Omar invites a different mother to situate her toddler on a cloth covered mat. After washing to model good hand hygiene, he kneels and speaks softly, showing the child leaves just plucked from the tree.

She sits frozen, eliciting laughter from the crowd.

Above: Gbiel sees how much her child benefits from play.

Above: Nurse Omar’s attempt to interest a toddler in leaf play makes the group laugh.

Another mother steps forward to take a turn, first washing up, then inviting her daughter to take interest in the leaf-toys. Nurse Omar’s praise is effusive, genuine. He is building trust, building up to more advanced lessons in this early childhood development series, some of which will guide parents to make more elaborate toys — like plastic bottle cars – using recycled and found materials .

Above: Parents in Siriyiri get creative with recycled and found materials.

(Photos in slideshow courtesy of Kate Holt/MCSP.)

In addition to caring for children, women have many chores in this village – collecting wood, pumping water, making meals, and farming – but, interestingly, the fathers of this community are game when it comes to play.

Above: Richard Gbare says, “A father can play to make a bond with his child.”

Richard Gbare, for instance, is attending this “mothers group” meeting even though today his own wife and baby are absent. They are away at the farm, he says.

“It’s not only the woman who is supposed to play with their children,” he says. “A father can play to make a bond with his child.”

His 26-month-old son likes football, Gbare reports, which just so happens to his favorite sport, too.

Despite no ball and no baby, Gbare gamely washes his hands and heads to the inner circle with a little girl temporarily borrowed from one of his neighbors. At Nurse Omar’s prompting, Gbare names her clothing — “a dress!” — and tenderly touches its fabric.

She smiles.

Above: With his own son absent, Gbare borrows a neighbor’s daughter for a demonstration.

A father of twins watches, admiring Gbare’s efforts. “The more intelligent and healthy and capable our children are,” he says, “the stronger the community today and tomorrow.”

Above: Supporting the future of the community.

<

Above: Video of a mom and baby playing.

Story, photos and videos by Maryalice Yakutchik,Communications Manager