On May 20th, two USAID flagship projects – the Maternal and Child Survival Program (MCSP) and the Evidence to Action Project (E2A) – jointly hosted an event focused on first-time parents (FTPs). The interactive forum was the latest in a series of efforts to explore the key issues related to work with this unique and often overlooked population.

Comprised of women under 25 years who are pregnant with or have one child, and their male partners, FTPs are a uniquely vulnerable population who often start their reproductive lives without the information and services they need. Reaching them with timely, continuous and lifesaving services and information can dramatically increase reproductive, maternal and child health.

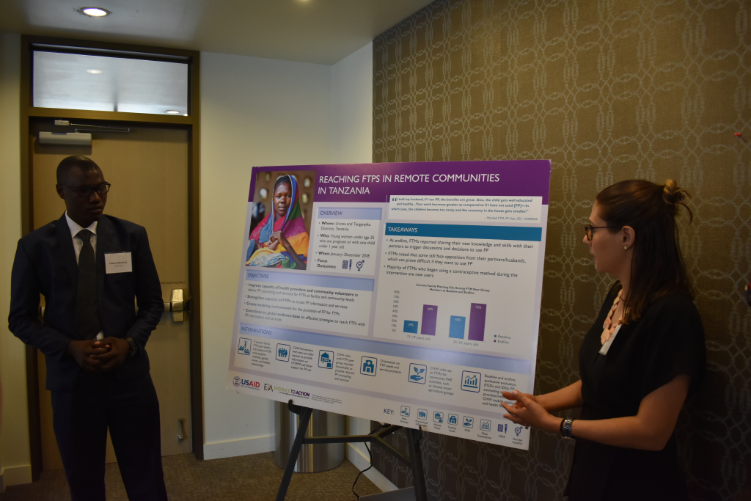

Over the past five years, our projects have gathered important experience with FTPs through six interventions in diverse settings: E2A in Burkina Faso, Nigeria, and Tanzania; and MCSP in Madagascar, Mozambique and Nigeria. In the process, we’ve gained new evidence on effective programs to meet their health needs.

Our collaboration in this educational event allowed us to look across these projects to identify common elements and persistent challenges. We hoped the day’s activities and discussions would trigger fresh thinking about specific priorities for advancing effective programming for FTPs. With the tremendous interest and energy in the room, we were not disappointed!

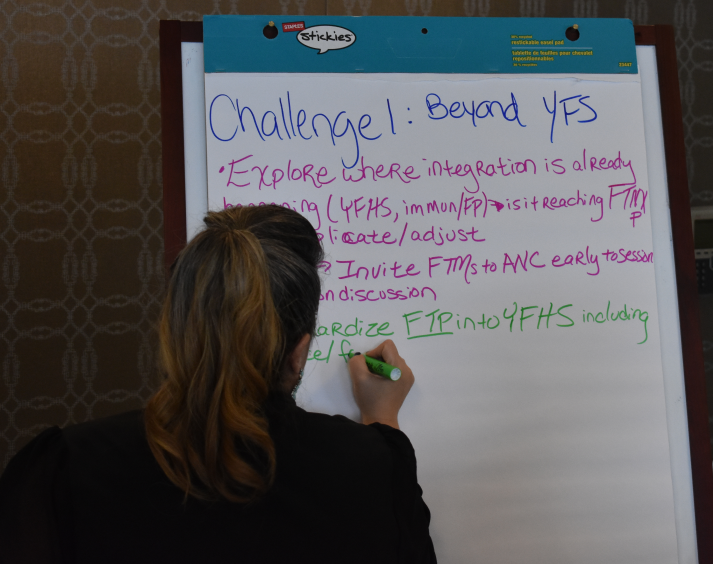

As 50+ colleagues delved into our findings and shared their own insights, three key priorities emerged and pointed to a way forward for FTP programs:

1. We must respond to a diversity of FTP profiles and experiences.

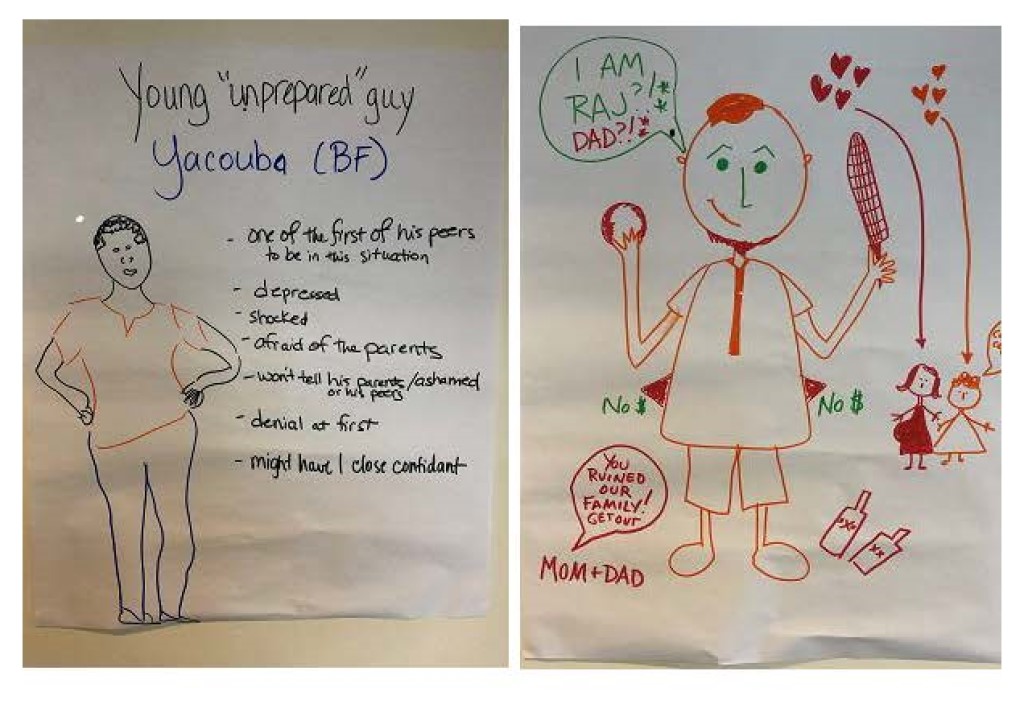

Although becoming a parent for the first-time may be universal, E2A and MCSP’s projects highlight just how diverse FTPs are – both in their backgrounds and in their experiences as they go through this lifestage. FTPs experience a spectrum of varied, sometimes conflicting emotions:

- Relief to have demonstrated fertility

- Fear of pregnancy and childbirth

- Compromised aspirations for the future

- Hope for the future of their child

This diverse experience is shaped by many factors; one is the nature of relationships with male partners. We reflected on how male partners are just as diverse as first-time mothers (FTMs) — while some are also young and becoming a parent for the first time, others may be much older, and still others already have one or more children. Some FTMs are in a committed relationship with their male partners at the time of pregnancy, while others may formalize their union when they become pregnant, and still others are abandoned by their boyfriends.

Understanding this diversity matters because it shapes decisions around health practices, including whether to seek care in a health facility. For MCSP and E2A, these insights revealed important considerations to help tailor programs to meet FTPs’ diverse, rapidly shifting needs.

2. We must help FTPs navigate the myriad challenges they face.

For FTPs, everything is changing. Beyond the rapid series of physical changes and health needs that come with pregnancy, delivery and caring for a newborn, this lifestage is also a time of dramatic social and relationship changes. FTMs may marry and move to their new husband’s village. They may drop out of school because pregnant girls are not allowed to attend. Younger and unmarried mothers may face shame and stigma from their families and communities. Many find themselves with little power over their health care choices, because such decisions are made by family members.

One FTM in Nigeria articulated these complex series of changes well: “I feel ashamed to face even my friends. Your peer group is looking at you, seeing you pregnant when you are not supposed to be, when you are in school and you were supposed to finish. I am a student, so this is very, very bad. I feel pressure from my dad and all of that, so it is quite disappointing.”

So, how do we help FTPs successfully navigate these transitions?

In communities and health facilities, FTPs need access to friendly, skilled providers and affordable care that meets their needs — before, during, and after pregnancy. In their daily lives, they need supportive families, peer groups, and communities that help to navigate these complex decisions and emotions. Moreover, beyond support for mothers and fathers as individuals, couples need support in navigating this experience together, including building communication skills.

FTPs need help to reframe their aspirations to reflect their changing context. They also need access to financial resources to be able to carry out their health care choices. This necessitates connections to education and livelihoods opportunities beyond the health sector.

Importantly, while most efforts to date have focused on support to FTMs, the transition that men experience as they become fathers is also a window of opportunity to reach them with information and services that meet their needs. Yet, few programs directly support men in assuming a positive co-parenting role, and many navigate this transition without positive role models for fatherhood.

A male partner in Nigeria described his worries about becoming a father: “How will I manage [to become] head of the family? As of now, I am not yet the head of [anything]. Somebody is feeding me and my wife. How will I be strong to feed [the baby] and feed myself and the mother?”

During the meeting, we tasked ourselves with continuing to design programs that meet the needs of interests of FTMs and their male partners — and with better supporting couples to navigate this time together.

3. We must generate context-specific evidence, especially from FTPs themselves.

Having solid evidence on the challenging situation, needs and aspirations of FTPs – and the resources, individuals and systems available to support them – is critical to tailoring program responses in diverse cultural contexts. Equally important is the evidence to demonstrate that we can advance meaningful outcomes for FTPs through well-designed, culturally-specific programs. Both sides of this evidence coin are crucial for this relatively new, but promising, field.

(Photo courtesy of Elizabeth Williams/E2A.)

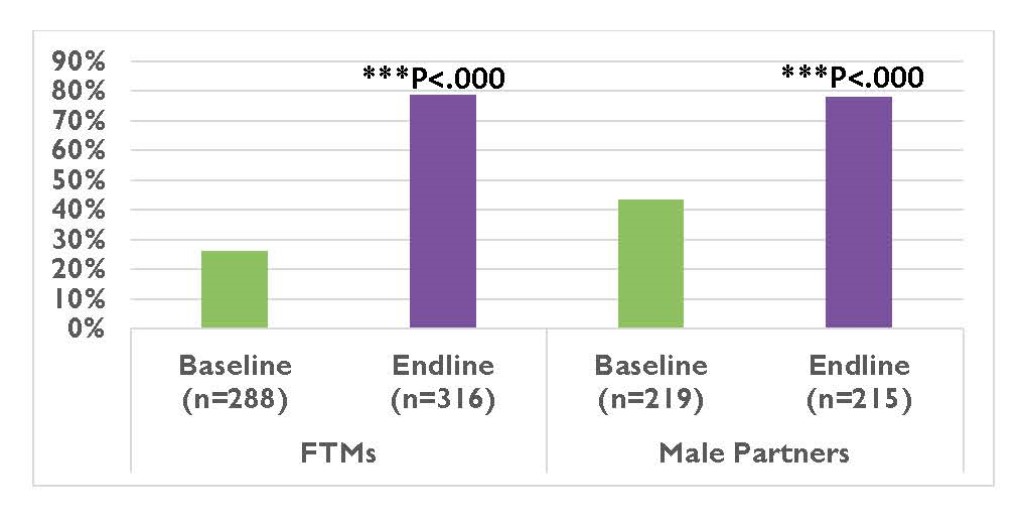

Throughout the day, having data from multiple projects – and from diverse FTPs – helped to fuel new conversations about the needs and opportunities of working with FTPs. New results emerging from Nigeria and Tanzania clearly demonstrate that important health outcomes can be achieved. For example, in Nigeria, voluntary use of family planning increased significantly over the course of the 4-month intervention. (See graph below.)

Even with relatively short, intense programs, we also saw positive changes in gender attitudes and couple dynamics, such as communication about family planning use. All of this underscores the tremendous potential of continued programming for FTPs to generate immediate results and potentially influence the longer-term health and well-being of these young people and their children. Programs must continue to invest in generating new evidence that continue to refine and advance meaningful FTP programs at greater scale.