Today, 19% of Rwandan women wish to delay or avoid pregnancy but are not using contraception. Focusing on reaching postpartum women – particularly those in the immediate postpartum period (within the first two days after birth) – is a high-impact practice that can effectively reduce this unmet need for family planning.

With this in mind, more than 100 participants from districts, partners and non-governmental organizations, the Ministry of Health (MoH), and other stakeholders met February 9th in Kigali to discuss “Scaling up Postpartum Family Planning (PPFP) in Rwanda.” Organized by USAID’s flagship Maternal and Child Survival Program (MCSP) in collaboration with the MoH, the workshop highlighted the remarkable progress the country has made in expanding PPFP interventions.

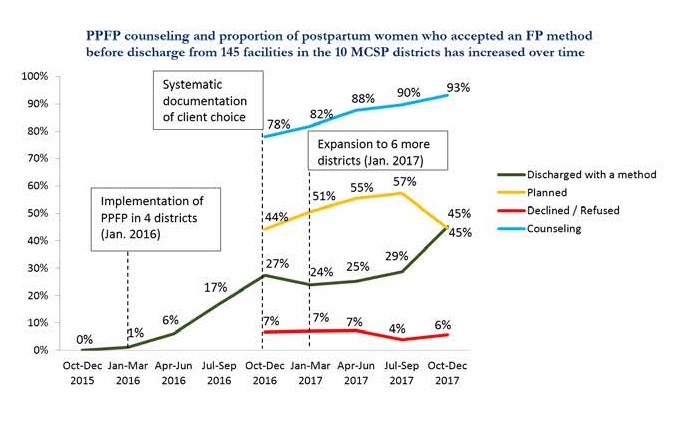

Since 2015, MCSP has worked with the MoH to roll out PPFP services in a phased process, following the ExpandNet/World Health Organization (WHO) approach to systematic scale‑up. Initially begun in four districts, MCSP scaled up to 10 districts in 2017. From 2015 to date, various partners – including MCSP, UNFPA, Partners in Health, and the MoH – have initiated PPFP interventions in 20 districts throughout Rwanda. Workshop participants planned key actions to maintain progress and expand PPFP to all 30 districts in Rwanda.

MCSP’s rollout of PPFP services involved building capacity of health providers, equipping facilities with supplies, and expanding PPFP services to cover all public facilities in supported districts. While there is a focus on provision of PPFP in the immediate postpartum period, the PPFP package is comprehensive. It begins in the antenatal period with counseling at facility and community antenatal care sessions and extends to integration of FP at various points of contact the woman and her child have with health services up to 12 months postpartum.

One health facility manager enthused: “In our facility, we have created opportunities for making sure that clients have counseling and can choose a PPFP method when they attend for antenatal care, in delivery, postpartum care, or immunization of their new babies.” Women who choose not to initiate PPFP that day may decline or may make a plan to start using contraception later, after more time for reflection or discussion.

The PPFP implementation strategy has several components, beginning with improved counseling during pregnancy. As a provider trained by the program explained, “PPFP should preferably be discussed with all women while they are still pregnant, since this allows them to choose immediate postpartum contraception without the need to make a hurried choice.”

The aim is to improve providers’ skills in furnishing a wide range of PPFP methods to suit women’s preferences. Competency-based training ensures that they are up to date on the latest version of the WHO’s medical eligibility criteria, which in 2015 expanded the range of methods that breastfeeding women can begin immediately after childbirth to include progestin-only pills and implants. PPFP training also equips providers to insert postpartum IUDs, a procedure that uses a different technique for insertion in a postpartum woman than in a woman who has not recently delivered.

The training has been transformative for some providers who were previously unable to offer women all appropriate FP methods after delivery. “I have inserted five IUDs. I don’t have to call for support,” explained an FP provider. “I used to feel bad that I did not know how to offer a wide range of FP methods. I have confidence now.”

Finally, the strategy incorporates quality improvement through ongoing mentorship. Proficient PPFP providers are oriented to become district PPFP mentors. In turn, mentors conduct monthly clinical mentorship visits to give technical support to providers to ensure they maintain their knowledge and skills.

In the 10 districts supported by MCSP, the program has trained 308 providers on PPFP counseling and equipped 320 providers with clinical skills to provide PPFP services. The program has also strengthened documentation of PPFP counseling and uptake, which was not routinely measured before the intervention.

Since implementation began in 2016, there has been a strong upward trend in postpartum women accepting FP after delivery prior to leaving the health facility. In the last quarter (October-December 2017), almost half (45%) of postpartum women in the 145 MCSP-supported public facilities that received the full PPFP intervention began using FP before leaving the health facility.

In particular, three actions have emerged as critical to sustainable scale up:

- Using data dashboards to monitor and maintain progress;

- Identifying leaders and managers at multiple levels; and

- Having a flexible planning process that incorporates ways to share learning and adapts accordingly.

The program introduced dashboards with a small set of key indicators so that health providers at the facility and district levels could review data regularly and keep progress on track. With the idea that every car with a dashboard also needs a driver, the program also identified focal people at facility and district levels to manage the scale-up process.

At the national level, a PPFP scale-up subcommittee of the FP technical working group, led by the MoH, was poised to identify and respond to district scale-up needs. Prior workshops – including a stakeholders’ workshop in December 2016 and a semi-annual experience-sharing workshop in September 2017 – gave stakeholders a venue to learn from each other, discuss ways to address common challenges, and plan for expansion to new districts. By bringing multiple implementing partners and donors together to learn from the MCSP experience, the MoH was able to leverage additional donor resources to expand immediate PPFP services in new districts and achieve progress towards its vision of nationwide coverage.

At the 2017 FP Summit in London, the government of Rwanda reaffirmed its commitment to help reach FP2020 goals to enable more women and girls to access contraceptives. The country appears on track to reach its FP2020 pledge to bring PPFP to all districts by 2020 – an impressive achievement in sustainable scale-up of PPFP.